insights

The Need for Speed in Drug Development: A Sponsor’s Guide to FDA Expedited Programs

Over the past few months, the complex, obscure, and winding road of drug development has been catapulted into the limelight due to the excitement and anticipation of approval for a COVID-19 vaccine. Suddenly, the world now has a general understanding of the mechanics behind standard FDA approval processes and the potential opportunity to significantly expedite these processes in emergency situations. However, the need for speed in drug development is not a novel concept.

It’s long been known that the standard duration and cost of drug development can present significant barriers to the delivery of promising new therapies for patients in need. In the US, it can take up to 10 years and ~$2.6 billion to bring a novel drug or biologic from concept to market[i][ii]. Fortunately, global Regulatory Authorities (including FDA) have recognized this undeniable need to establish pathways that accelerate patient access to therapies intended for serious and life-threatening conditions.

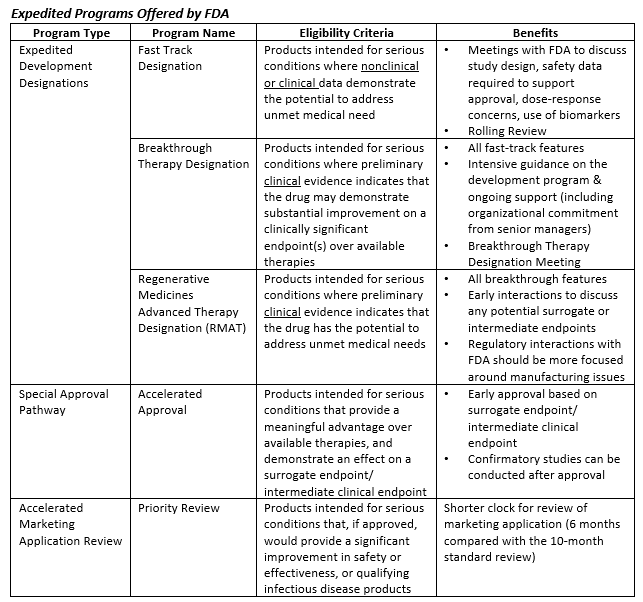

In the past ~25 years, FDA has developed and implemented a variety of expedited programs aimed at facilitating more rapid development and approval of therapies intended for critical and unmet medical needs. Some of these programs have been offered for decades, while others have been launched only in the past few years. In aggregate, the programs tend to fall into three primary categories: expedited development designations, special approval pathways, and accelerated marketing applications reviews. These programs are summarized below.

Utilization of these programs has been steadily increasing since deployment – 73% of novel drugs approved by FDA in 2018 were designated under at least one expedited development program[iii]. Despite this statistic, it’s important to note that the pursuit of these programs does not always guarantee success. Through 2019, CBER and CDER granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation (BTD) for less than half of the BTD applications they received[iv][v]. Understanding when, how, and why to apply for these various programs is critical to successful deployment. Moreover, it is essential for sponsors to consider FDA’s evolving thinking on this topic and to stay abreast of new initiatives that further augment the landscape of accelerated drug development.

Continued Innovation

In addition to the five expedited programs detailed above, FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE) has recently introduced additional mechanisms to further expedite marketing application review for novel oncology products. In 2018, the OCE launched a pilot program for their “Real-Time Oncology Review” (RTOR) and “Assessment Aid” (AA). The key advantage of these programs is that they facilitate submission of discrete application components prior to the pre-submission meeting (i.e. pre-NDA/pre-BLA) and well in advance of the final submission of the marketing application. The RTOR timeline allows FDA and sponsors to work collaboratively to flag and address critical issues/questions earlier in the process – those issues could relate to data quality, data analysis, and key regulatory questions. Additionally, the AA is a set of documents intended to supplement the RTOR program by facilitating the provision and evaluation of key information using a standard FDA format. Participating sponsors receive discipline-specific templates (e.g. Clinical, CMC) based on FDA’s own multi-disciplinary review format. These documents are then submitted during the RTOR process. When written concisely, the AA aids in consistency, increases review efficiency, and reduces time spent on administrative tasks (e.g. transcription performed by FDA).

Another innovative FDA OCE initiative is Project Orbis, which provides a framework for concurrent submission and review of oncology products among a coalition of international partners. The goals of this initiative are to achieve effective collaborative review of parallel applications to reach consensus in all participating countries, and to identify regulatory divergence across review teams to drive future harmonization. To date, FDA has collaborated most frequently with Health Canada (HC) and the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) on Project Orbis-related work; other countries have begun participating more recently. The first Project Orbis action took place in September of 2019, when HC, TGA (Australia), and FDA collaborated on a supplemental NDA to approve LenvimaTM (in combination with Keytruda) for the treatment of patients with advanced endometrial carcinoma[vi]. Following this approval, FDA has expanded the pilot program to include original applications.

Since the inception of RTOR and Project Orbis, the OCE has been quite busy piloting these programs. By mid-2020, there were 2 NME approvals conducted under RTOR, 11 supplemental NDAs, and 7 supplemental BLA approvals. The median time to approval for these applications was 3.3 months, with some (supplemental applications) being approved in less than a month[vii]. Similarly, Project Orbis has facilitated more than 38 product approvals across multiple countries. While these programs do present unique challenges for participating sponsors, it’s clear that they also offer promising opportunities to further accelerate the delivery of novel oncology therapies to underserved patient populations.

Unintended Consequences

It is not uncommon for products to be eligible for more than one expedited program. Not surprisingly, programs granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation are three times more likely to be granted Accelerated Approval (as compared to non-BTD programs[viii]). The application of multiple expedited programs affords sponsors the opportunity to significantly reduce overall product development time (i.e. time from IND submission to marketing application). For example, certain oncology products granted BTD and approved under Accelerated Approval moved from IND submission to NDA approval in approximately 4 years, or less. Such rapid development can put a major strain on CMC (chemistry, manufacturing and controls) teams to keep pace and deliver a commercial-ready product in short order.

Importantly, the pace of development does not fundamentally change the regulatory expectations or required marketing application content. Consequently, it is imperative for regulatory teams to consider the impact of expedited programs very early on in the product development planning process. If the regulatory and/or business strategy include the planned pursuit of one or more expedited program(s) then the CMC teams should be planning for accelerated development well in advance of receiving designations. Otherwise, these sponsors may not be well positioned to move things into the fast lane if/when designations are granted.

In order to offset CMC-specific challenges associated with accelerated development, sponsors should invest early in manufacturing and analytical development activities and pursue frequent interaction with FDA to negotiate risk-based approaches to the overall product development plan. Flexibility on the type and extent of the CMC information expected at the time of the initial marketing application will depend on process knowledge, a product-specific control strategy, and effective collaboration with the Agency. Opportunities for risk-based approaches to CMC development for expedited programs may include:

- Utilization/inclusion of expanded in-process and end-product testing at product launch to compensate for limited manufacturing experience and batch data. This expanded testing regimen may be reduced post-approval based on the accumulation of a broader data set.

- Non-traditional approaches to the provision of stability data supporting re-test and shelf-life periods for initial product launch. These approaches may be supported by the implementation of additional accelerated studies and the use of modeling to demonstrate product stability in the absence of a traditional (i.e. 12 month) data set for registration batches.

- Process validation and inspection planning should also be considered. With prospective alignment with FDA it may be possible to decouple the validation campaigns for drug substance and drug product thereby reducing the overall timeline. Separately, concurrent validation approaches may be viable for orphan designated products. For inspections, sponsors should discuss manufacturing timelines with the Agency prior to (or during) the pre-submission meeting(s) so that inspections may occur early under accelerated review processed (e.g. Priority Review).

Ultimately, the goal of the CMC development program is still to ensure consistent production of a safe and effective commercial product. While this objective remains unchanged for CMC teams ushering products through expedited development, they must do so with highly careful planning and a heightened sense of urgency.

Conclusion

Judging from headlines today, it could be easy to assume that Health Authorities have just recently figured out how to accelerate their approval timelines. However, a look back at the history of expedited review programs indicates that the pace and urgency associated with the development of a COVID-19 vaccine is the product of years of innovation – it didn’t happen overnight. While the losses associated with the today’s coronavirus pandemic far outweigh the wins, perhaps we’ll look back on this era as one that spurred another bolus of regulatory process innovation. There will always be a need for speed, and it will take true collaboration between sponsor companies and health authorities to keep a foot on the gas.

[i] PhRMA. Biopharmaceutical Research and Development. 2015. http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/rd_brochure_022307.pdf

[ii] DiMasi, J.A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.012

[iii] 1 United States Food and Drug Administration. “Novel Drug Approvals for 2018”. FDA.gov. Last updated: November 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2018

[iv] United States Food and Drug Administration. “CDER Breakthrough Therapy Designation Requests”. FDA.gov. Last updated: October 8, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/ind-activity/breakthrough-therapy-designation-requests

[v] 2 United States Food and Drug Administration. “CBER Breakthrough Therapy Designation Requests”. FDA.gov. Last updated: October 2, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/food-and-drug-administration-safety-and-innovation-act-fdasia/cber-breakthrough-therapy-designation-requests

[vi] https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-orbis

[vii] de Claro, A., et al. Initial Experience with the Real-Time Oncology. U.S. FDA. 2020. American Association for Cancer Research

[viii] DiMasi, J.A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.012